Mind Matters

Mind Matters

An Occasional Column by Anthony D. Fredericks

Designing a College Course

As a new professor, you may want to include everything about your discipline in your course, but realize that you have a limited amount of time or limited resources to do so. Designing a college course also means designing specific (manageable) goals and outcomes that give you and your students both direction and accomplishment. The result can be a learning adventure full of great memories. Let’s take a look.

As a new professor, you may want to include everything about your discipline in your course, but realize that you have a limited amount of time or limited resources to do so. Designing a college course also means designing specific (manageable) goals and outcomes that give you and your students both direction and accomplishment. The result can be a learning adventure full of great memories. Let’s take a look.

There are two critical questions that confront every college teacher – whether novice or experienced. Your response to these two queries will determine, in large measure, the success you enjoy as an adjunct professor and the academic success students will enjoy in your courses. They are crucial in the design of every effective course – from introductory freshmen courses to graduate seminars. They are:

| Question | Term | Definition |

| ‘What will I teach?” | Goals | These are the ideas, principles, concepts, or questions that you want to include in a course or that you want to teach. They are the end products of a course. |

| “What will students learn?” | Outcomes | Outcomes are what students will learn as a result of their exposure to those course goals. They are the skills that students develop throughout a course. |

One of the classic errors many adjunct professors make is that they tend to concentrate on the first question almost to the exclusion of the second question. That is to say, they spend a lot of time planning what they will teach in their courses, but insufficient time on what they plan to have students learn in those courses. Many adjunct professors, particularly those fresh from graduate school, have all the latest theories, statistics, research, and content about a particular discipline. They often spend an inordinate amount of time trying to “fit” that content into the parameters of a fifteen-week semester. Little thought is given to the “learnings” they want students to have at the conclusion of that course.

Reframing the Questions

One of the ways to begin designing your courses is to reframe the questions above. Instead of asking yourself, “What will I teach?” consider these two modifications:

- What do students need to know?

- What will they be able to do with that knowledge?

This reframing of the initial questions provides you with two critical focal points. It helps you zero in on the necessary content in concert with the utility of the content in students’ lives. If your sole goal is to have students memorize the content (the traditional approach) then you are eliminating a critical component of the teaching/learning paradigm. That is, what do you want them to do with their newfound knowledge? In short, teaching is about changing – changing students’ minds, changing their perceptions and outlooks, and changing their interpretations of the world. Giving them knowledge is one thing; giving them opportunities to use that knowledge is the sine qua non of a good college course.

Course Introduction

Before you write a course syllabus, give some thought to constructing a course introduction (frequently the initial paragraph in many course syllabi). By focusing on the goals and outcomes of a course in your course introduction you will be able to address the two critical elements of any subject – what will you teach, what will they learn? Everything else in the course can stem from the answers to these two initial queries.

Let’s say you’re designing a course entitled “Survey of the Music Industry.” Now, here’s a course chock full of information and details! Potential topics include: career planning, creative careers, producing/directing, performing, teaching, songwriting, music publishing, copyright registration, sources of royalty income, performance rights, music licensing, the role of unions, music associations, arts administration, talent agencies, and artistic management. That’s a lot of stuff for one course! How do you get it all in? My suggestion – don’t try to.

In trying to “fit” all that information into a single course you will have a tendency to ignore or eliminate student outcomes for the sake of (or at the expense of) all your planned goals. Here’s a sequence of activities that will help you respond to the two critical questions above (while also maintaining your sanity):

- Make a list of all the goals, concepts, or principles that are part of the course. These can be obtained from your own experiences, a planned course textbook, suggestions from colleagues, or research. You can begin drafting your list of goals by providing answers to some of the following self-directed queries:

- What is important for students to know?

- What topics interest me the most?

- What concepts should I emphasize?

- What is the main idea of this course?

2. Identify the three most critical goals. These should be more general than specific. For example, “The mental processes and structures that compose the human cognitive system” rather than “The retrieval of memory.”

3. Make a list of all the outcomes you want for your students. You can begin drafting your list of outcomes by providing answers to some of the following self-directed queries:

- What do I want students to be able to do by the end of the course?

- What new skills will students have after this course?

- How will students’ thinking be changed by this course?

- What student perceptions or misperceptions do I want to challenge?

4. Select the two most critical outcomes. Be sure these are framed in terms of what students will be able to do with the information you provide them. For example, “Students will be able to use standard methods of solving ordinary differential equations and apply them to physics.”

5. Design a one-paragraph introduction to the course which incorporates the three goals and two outcomes. You may wish to direct this introduction to students (“By the end of the course, you will be able to….”) or you may wish to keep it impersonal (“This course is an introduction to the principles of ….”). Make this introduction the opening paragraph of your course syllabus.

You may argue that three goals and two outcomes are insufficient for your subject or course. I realize that most courses involve an overwhelming plethora of principles, concepts, factual information, and issues. But, the key here, especially in initial course design, is simplicity. It’s also to provide you with a manageable plan, one that helps you keep your focus without losing your way. Inevitably, you will deal with many issues and concerns throughout the semester, but the 3-2-1 plan will provide you with a reliable compass as you begin to design that course.

Know, too, that as you progress through your teaching career you will refine, hone and sharpen your course design. Suggestions from colleagues, ideas from periodicals and journals, research, conference proceedings, and other information sources will all become part of your courses. For now, you just need a solid platform on which to stand. Don’t try to do everything the first time “out of the blocks.” Keep the plan manageable, simple and straight-forward. Remember that good courses and good instructors are always evolutionary. Start with a simple plan and then, as you add to your experience base, adjust and modify the course accordingly.

_____________________

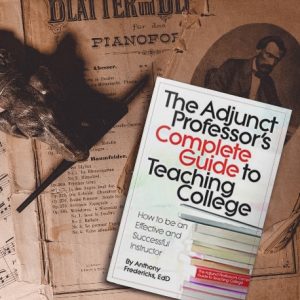

Dr. Anthony D. Fredericks is Professor Emeritus of Education at York College of Pennsylvania (and a former adjunct professor). He is an award-winning author of 175+ books, including The Adjunct Professor’s Complete Guide to Teaching College (“[The author] covers all the bases, from designing your course and syllabus to first day impressions to course evaluation.” * * * * *)

Dr. Anthony D. Fredericks is Professor Emeritus of Education at York College of Pennsylvania (and a former adjunct professor). He is an award-winning author of 175+ books, including The Adjunct Professor’s Complete Guide to Teaching College (“[The author] covers all the bases, from designing your course and syllabus to first day impressions to course evaluation.” * * * * *)

To see more books by Dr. Anthony D. Fredericks or others published by Blue River Press, go to our Book Shop. If you have any questions, you can contact us here or call us at 317-352-8200